It Didn’t Start With Violence

On Anne Frank, Memory, and Paying Attention

This morning I went to the Center for Jewish History in New York to visit the Anne Frank Exhibit. I was a teenage girl myself when I first decided Anne Frank was one of my heroes. A classmate scoffed at the idea. “Why a teenage girl?” he asked. I wanted to throw something at him. What he meant was her thoughts didn’t matter because she hadn’t invented anything, hadn’t survived, hadn’t made history beyond noticing the world. What I understood immediately was that paying attention, writing it down, and trusting that your inner life mattered was a kind of courage all its own.

Anne was born in 1929, the same year as my grandfather, the same year as Martin Luther King Jr., whose birthday I share. I was a teenage girl with a diary, aspiring to be a writer, living out loud in simple ways that Anne could never risk. She wrote that despite everything, she still believed people were good. I struggle to share that opinion, even now, and yet reading her words feels like a small rebellion, a reminder of what courage can look like in the quietest forms.

I asked my brother to go with me, though we experience history differently. I read everything; he reads little. But history isn’t a niche interest. It belongs to the people who were captivated by Anne Frank at first glance and to the people who only half remember her name from school. It doesn’t ask permission before repeating itself. It rarely announces itself as brutality at first.

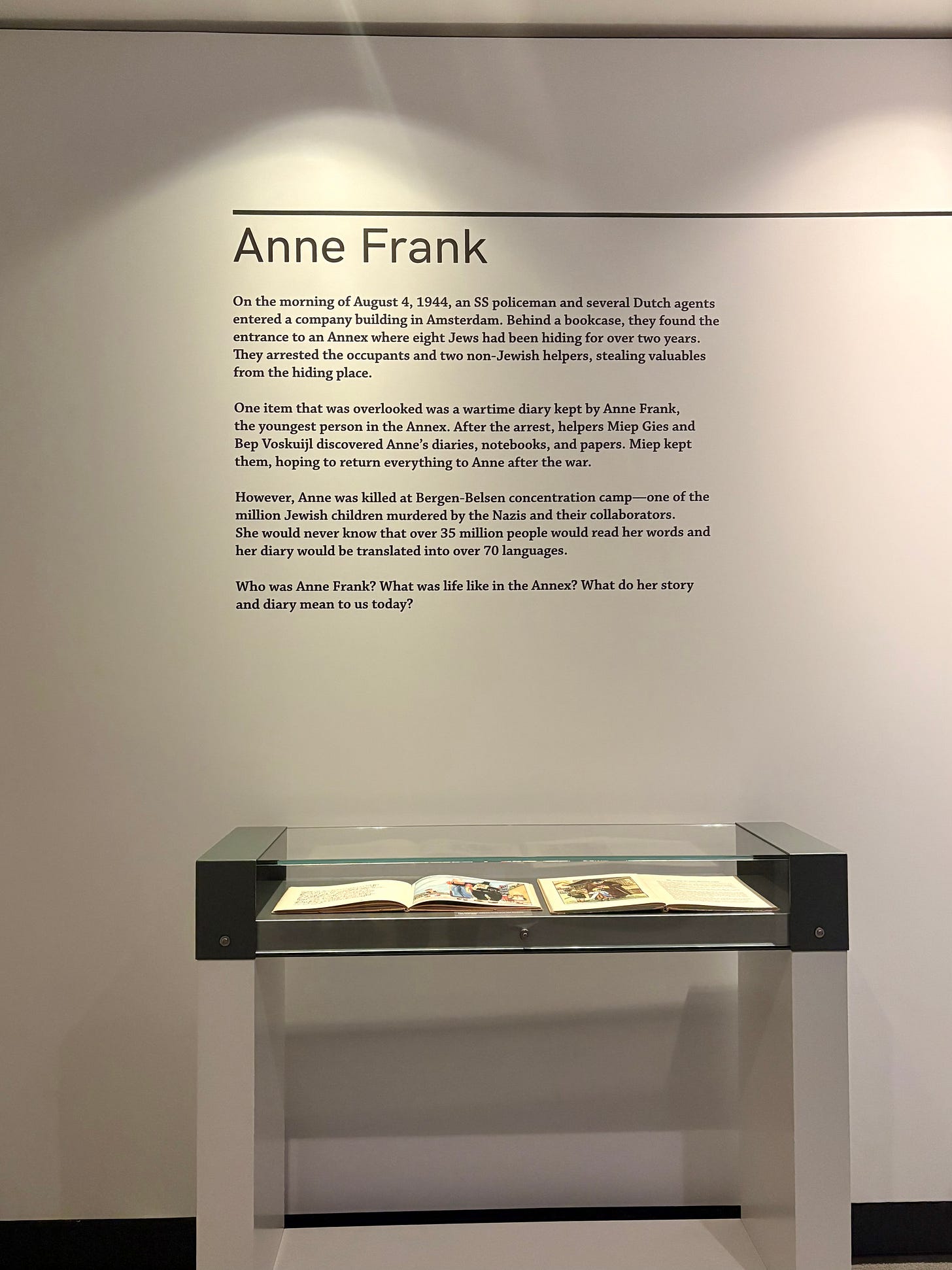

The exhibit traces Anne’s life from her parents’ early years through Hitler’s rise to power, following the family toward the point where hiding became their only option. Before stepping into a recreation of the Annex where the Franks, van Pelses, and Fritz Pfeffer hid, the exhibit lays out the years 1939 to 1942, when the Franks were still living openly, and how Jewish people were stripped of rights, identity, and dignity step by step, law by law, day by day. The video panels, photos, and documents make the gradual machinery of oppression terrifyingly clear. That’s what hits me the hardest: it didn’t start with violence, it started with paperwork, decrees, and compliance.

Otto Frank had tried to get the family to America. He’d even interned at Macy’s around 1910, so he knew the place. But visas were denied. They were trapped, and the Annex was both refuge and cage. Living on top of one another for more than two years, silent so that workers below didn’t hear, there was no privacy and no escape. Anne shared her room with a man old enough to be her father. It must have been suffocating, yet she pasted Hollywood stars to the walls, tucked her hopes into a diary, and carried the ordinary rituals of a teenager’s life into impossible circumstances. I taped posters to my walls in much the same way. That’s what drew me to her all those years ago when I was her age: the ordinary teen, surviving extraordinary terror.

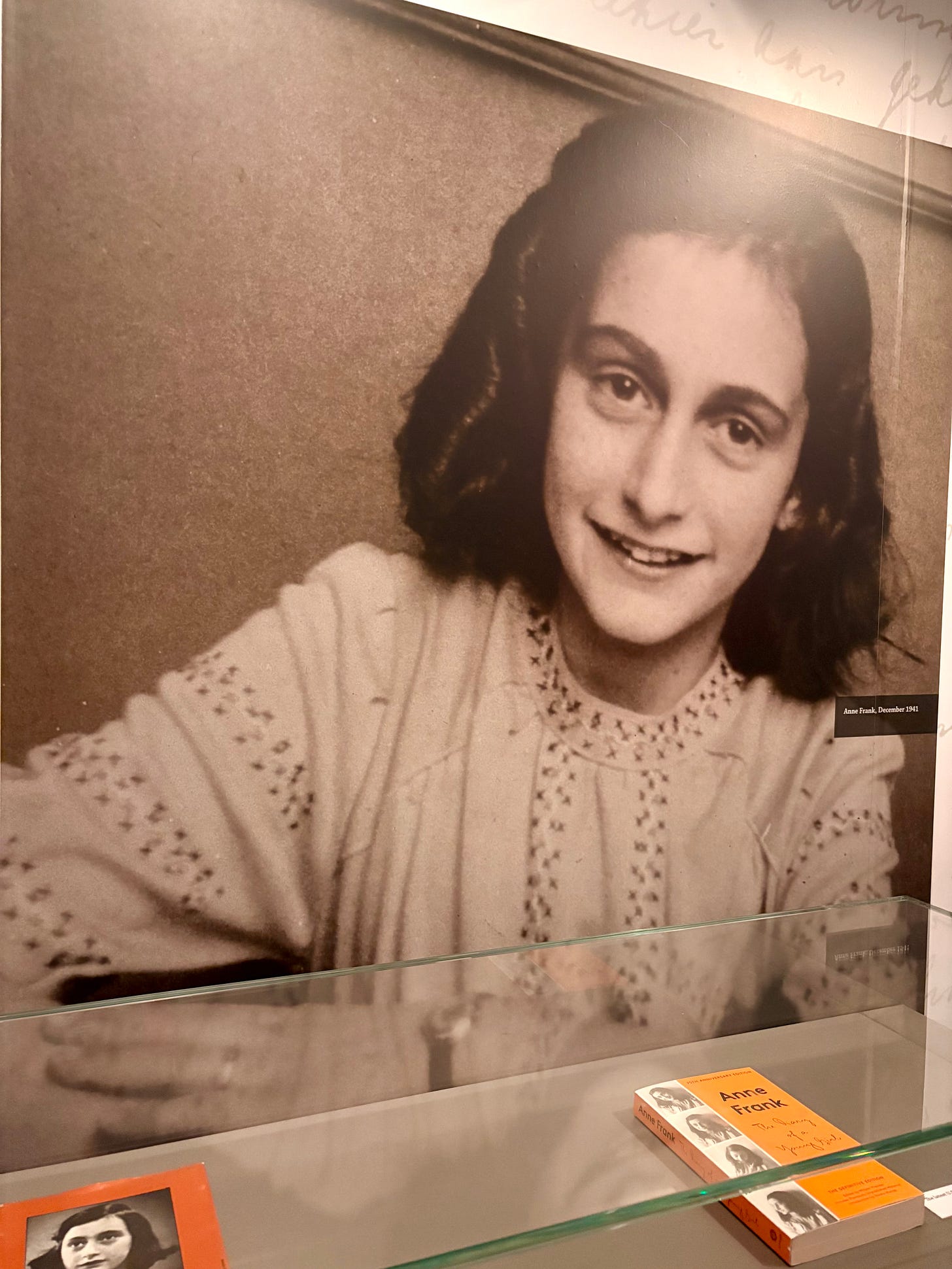

There’s a photograph of Otto Frank standing alone in the empty Secret Annex. The rooms are empty. He is looking off-camera, as if the photographer interrupted a private reckoning. That photo has always stayed with me, and it is shown here at the end of the exhibit, next to a glass case displaying all of the different editions and translations of Anne’s diary.

Otto Frank was the only member of his family who came back. He remarried. His stepdaughter, Eva Schloss, had been friends with Anne. She died on January 3 of this year. Miep Gies, who hid the Frank family and preserved Anne’s diary, is gone. Hannah Pick-Goslar, Anne’s childhood friend, is gone. Their names matter. Survival is not abstract; it is specific. And history is carried forward by those who live, remember, and name.

As we stood outside waiting for an Uber, I whispered to my brother how terrifying it is that it could happen again. He said it wouldn’t. People wouldn’t allow it. I wanted to ask him how many people had allowed it last time, but instead I nodded and let the conversation end.

If anything today’s world shows, it’s that those in power make the same mistakes at the expense of the powerless. Paying attention matters. Naming names matters. Remembering matters.

Anne Frank didn’t survive, and survival is no guarantee of clarity or goodness. But some people do survive, and in doing so they bear witness: quiet, persistent, painful. Some people are good. And they have names.

The part of Anne's heart-wrenching quote that just guts me every time are these words: "In spite of everything..." To me, this signals her fight to live and to believe that the horrors would end. That word "spite" shows her fiery spirit. But then that word "everything" just brings me to my knees. What a reminder that what we're going through in the US right now is not even close to what she went through just trying to live another day. And her overall idea of hope is what overwhelmingly resonates today. We still have that, so not all is lost. Yet.

😞